Mark Kopec Now

C-section

The Double-Edged Sword: C-Sections and Medical Malpractice

The birthing process is often a joyous occasion. However, it is also a complex medical event that carries inherent risks for both mother and child. While most births proceed without major complications, there are instances where medical intervention becomes crucial. Among these interventions, the Cesarean section, or C-section, stands as a procedure that has improved maternal and infant outcomes. However, like any medical procedure, it has its own set of potential pitfalls. A delayed or improperly performed C-section can lead to devastating birth injuries. The C-section can form the basis for medical malpractice claims.

A Glimpse into History: The Evolution of the C-Section & Medical Malpractice

The history of the C-section is as fascinating as it is long, tracing its roots back to antiquity. Early accounts were often legend. They describe desperate attempts to save the infant when the mother had died or was dying. Roman law included the Lex Regia (later Lex Caesarea, which the term “Caesarean” may derive. Although its exact etymology could also relate to the verb “caedere” meaning “to cut”). It mandated that if a pregnant woman died, the attendant should open her abdomen to save the child. These early procedures were almost exclusively post-mortem on the mother. Survival of both mother and child were extraordinarily rare.

For centuries, the C-section remained a last resort, primarily due to the overwhelming risk of infection and hemorrhage. Without anesthesia, sterile techniques, or understanding of surgical anatomy, survival rates for the mother were abysmal. It wasn’t until the 16th century that the first documented case of a mother surviving a C-section in Europe occurred. Jacob Nufer performed it on his wife. However, this remained an isolated incident, and the procedure continued to have extreme danger.

The 19th century brought significant advancements that began to transform the C-section into a viable, though still highly risky, procedure. The introduction of anesthesia in the mid-1800s provided pain relief. The development of antiseptic techniques by Joseph Lister dramatically reduced post-surgical infection. Perhaps the most pivotal breakthrough came with Max Sänger’s innovation in 1882. The technique of suturing the uterine wall after delivery. This significantly controlled hemorrhage and reduced the risk of rupture in subsequent pregnancies. The 20th century witnessed further refinements, including blood transfusions, antibiotics, and improved surgical instruments and techniques, solidifying the C-section’s place as a surgical option.

What is a C-Section?

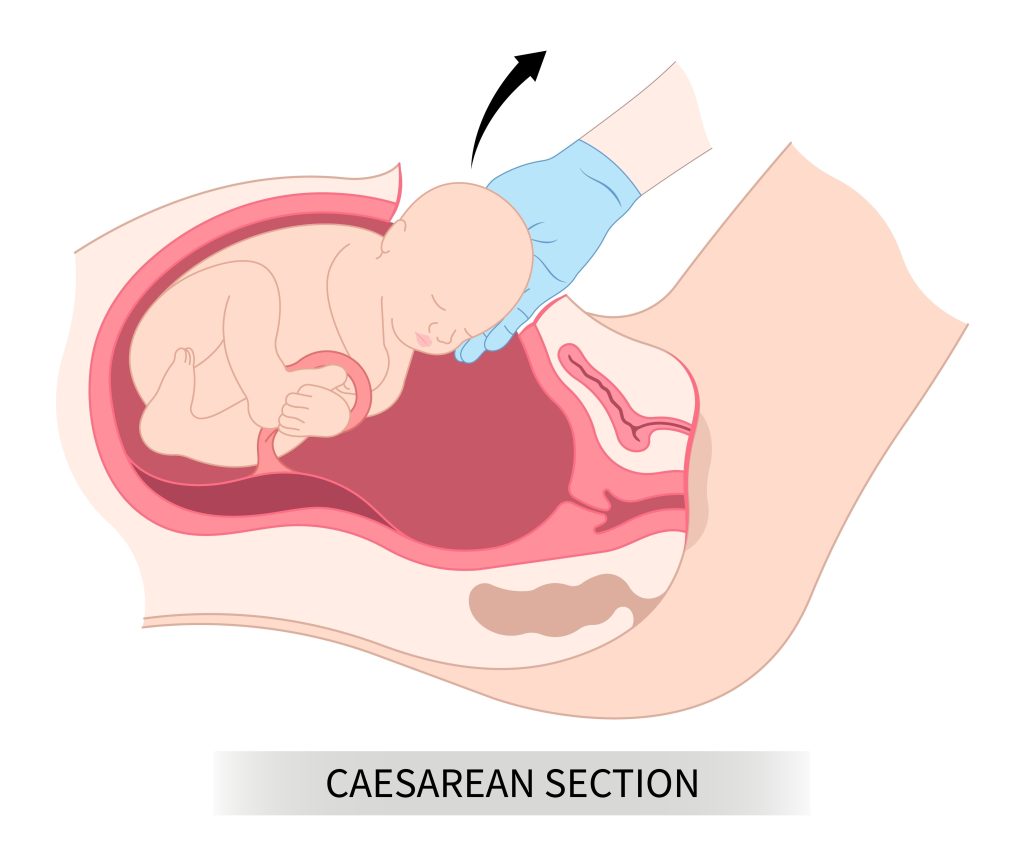

A C-section is a surgical procedure in which a baby is delivers through an incision. The incision is in the mother’s abdomen and uterus. This procedure is instead of birth through the vaginal canal. It is an abdominal surgery and is typically when a vaginal delivery poses risks to the mother or baby that outweigh the risks of surgery.

How is it Performed and Who Performs It?

An obstetrician-gynecologist (OB/GYN), a medical doctor specializing in women’s health and childbirth, usually performs the procedure. In some complex cases, other surgical specialists may join in. The surgical team typically includes doctors and other providers, such as an anesthesiologist, surgical nurses, and often a neonatologist or pediatrician to care for the newborn immediately after delivery.

The procedure generally follows these steps:

- Anesthesia: The mother receives anesthesia, typically a regional anesthetic like an epidural or spinal block. This numbs the lower half of her body while allowing her to remain awake and aware during the birth. In emergency situations, doctors may use general anesthesia.

- Preparation: The medical team cleans the abdomen with an antiseptic solution and places a sterile drape. The team inserts a catheter into the bladder to keep it empty during surgery.

- Incision: The surgeon makes an incision through the abdominal wall. Most commonly, the doctor makes a low transverse incision (often called a “bikini cut”) horizontally across the lower abdomen, just above the pubic hairline. In some emergency situations, a vertical incision may be necessary.

- Uterine Incision: Once the doctor separates the abdominal layers, they make a second incision in the uterus. Again, a low transverse uterine incision is most common, as it bleeds less and heals better than a vertical incision.

- Delivery of the Baby: The surgeon carefully reaches into the uterus and delivers the baby, typically head first. Then they clamp and cut the umbilical cord.

- Placenta Delivery: After the baby is delivered, the placenta is removed from the uterus.

- Closure: The uterus is meticulously sutured closed in several layers. The abdominal layers are then closed with sutures or staples.

Indications for a C-Section

C-sections can be planned (elective) or unplanned (emergency). The decision to perform a C-section involves various factors. These include the mother’s health, the baby’s health, and the progression of labor.

Common Indications for a C-section Include:

- Failure to Progress (Dystocia): This is one of the most common reasons for an emergency C-section. It occurs when labor stalls or progresses too slowly, despite strong contractions. This can be due to a large baby, a small pelvis, or an ineffective labor pattern.

- Fetal Distress: If the baby is not tolerating labor well, indicated by abnormal heart rate patterns (e.g., persistent decelerations), a C-section may be necessary to prevent oxygen deprivation.

- Breech Presentation: When the baby is positioned feet-first or buttocks-first instead of head-first. While some breech babies can be delivered vaginally, C-section is often recommended to reduce risks.

- Multiple Pregnancies: C-sections are more common with twins, triplets, or more. Especially if the babies are not in optimal positions or if there are other complications.

- Placenta Previa: A condition where the placenta partially or completely covers the cervix. It blocks the baby’s exit and potentially causes severe bleeding during labor.

- Placental Abruption: When the placenta separates from the uterine wall prematurely, which can lead to severe bleeding and fetal distress.

Additional Indications

- Cord Prolapse: A rare but critical emergency where the umbilical cord slips into the vagina before the baby, potentially compressing the cord and cutting off oxygen supply.

- Previous C-Section: While many women can attempt a vaginal birth after C-section (VBAC), some factors may necessitate a repeat C-section.

- Maternal Health Conditions: Certain maternal medical conditions, such as severe preeclampsia, active genital herpes, uncontrolled diabetes, or significant heart disease, may make a vaginal delivery too risky.

- Macrosomia: When the baby is estimated to be very large, increasing the risk of shoulder dystocia or other birth injuries during a vaginal delivery.

Birth Injuries from Delayed C-Section: A Medical Malpractice Concern

While a C-section carries its own risks, failing to perform one when medically indicated, especially in an emergency, can lead to severe and permanent birth injuries. Medical malpractice claims in this context often center on the argument that a reasonable and prudent obstetrician would have recognized the signs necessitating a C-section and acted promptly. A delayed C-section can deprive the baby of oxygen and blood flow, leading to a cascade of complications.

Critical Birth injuries That Can Result from a Delayed C-Section Medical Malpractice:

Cerebral Palsy (CP):

What it is: Cerebral palsy is a group of disorders that affect a person’s ability to move and maintain balance and posture. It is caused by abnormal brain development or damage to the developing brain, often occurring before or during birth. The symptoms can range from mild to severe and include muscle stiffness (spasticity), tremors, problems with coordination, and difficulties with speech and swallowing.

How delayed C-section causes it: Prolonged or severe oxygen deprivation (hypoxia or asphyxia) to the baby’s brain during labor is a primary cause of certain types of cerebral palsy. If a C-section is delayed when the baby is showing signs of distress (e.g., abnormal fetal heart rate patterns indicating oxygen deprivation), the brain may suffer irreparable damage. This can occur, for instance, if the placenta detaches (abruption), the umbilical cord is compressed (prolapse), or labor is prolonged with fetal distress, and the medical team fails to recognize the urgency and expedite delivery via C-section. The longer the brain is without adequate oxygen, the greater the extent of the damage and the higher the likelihood of developing CP.

Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy (HIE):

What it is: HIE is a type of brain damage that occurs when the brain doesn’t receive enough oxygen and blood flow for a period of time. It can range from mild to severe, affecting various parts of the brain. While CP is a long-term outcome, HIE describes the acute injury to the brain.

How delayed C-section causes it: Perinatal asphyxia is a lack of oxygen during or around the time of birth. It causes HIE. If a C-section is delayed when there’s an acute event threatening the baby’s oxygen supply, such as a severe placental abruption, uterine rupture, or cord prolapse, the baby’s brain can quickly become deprived of oxygen and blood. This lack of oxygen kills brain cells, leading to swelling and further damage. The degree of HIE is often directly correlated with the duration and severity of the oxygen deprivation, making prompt delivery via C-section crucial in such scenarios.

Periventricular Leukomalacia (PVL):

What it is: PVL is a form of white matter brain injury primarily affecting premature infants, but it can also occur in full-term infants who experience significant periods of hypoxia-ischemia. It involves damage to the white matter of the brain, specifically around the ventricles, which are responsible for transmitting signals throughout the brain. This damage can lead to motor and cognitive impairments.

How delayed C-section causes it: Similar to HIE and CP, PVL triggers by a lack of oxygen and blood flow to the brain. In situations where a premature baby is experiencing distress and requires an urgent C-section, a delay can exacerbate the existing vulnerability of the premature brain to oxygen deprivation. The developing white matter is particularly susceptible to damage from hypoxia-ischemia, and a prolonged period without adequate oxygen due to a delayed C-section can lead to the characteristic lesions of PVL.

Umbilical Cord Compression Injuries:

What it is: Umbilical cord compression directly causes these injuries. This restricts the flow of oxygen and nutrients to the baby. This can manifest as various degrees of brain damage, HIE, or even fetal demise (and a wrongful death claim) if the compression is severe and prolonged.

How delayed C-section causes it: Umbilical cord prolapse is where the cord slips ahead of the baby and compresses between the baby’s head and the mother’s pelvis. It is a dire emergency. In such cases, the oxygen supply to the baby can become severely compromised within minutes. A delayed C-section with a cord prolapse can be catastrophic, as every minute counts in restoring oxygen flow. Nuchal cords are cords wrapping around the baby’s neck. Similarly, they can occasionally cause compression during labor. If doctors ignore signs of fetal distress, a delayed C-section can lead to significant oxygen deprivation.

Brachial Plexus Injuries (Erb’s Palsy, Klumpke’s Palsy):

What it is: The brachial plexus is a network of nerves that controls movement and sensation in the arm and hand. Injuries to these nerves, such as Erb’s palsy (affecting the upper arm) or Klumpke’s palsy (affecting the lower arm and hand), often occur during difficult vaginal deliveries due to excessive pulling or stretching of the baby’s head and neck relative to the shoulders.

How delayed C-section causes it: While primarily associated with vaginal delivery, a delayed C-section can indirectly contribute to these injuries. It can allow a prolonged and difficult labor to continue when the doctor clearly should do a C-section. An example involves a large baby (macrosomia). Signs of shoulder dystocia (the baby’s shoulder stuck behind the mother’s pubic bone) can occur during a trial of labor. Delaying the C-section in favor of continued attempts at vaginal delivery can increase the risk of brachial plexus injuries as practitioners employ maneuvers to free the shoulder, potentially causing nerve damage.

Conclusion on C-Section Medical Malpractice Birth Injury

The C-section remains an important intervention. However, the decision to perform a C-section, and the timing of that decision, is paramount. When medical professionals deviate from the accepted standard of care, they can delay a necessary C-section. The consequences for the newborn can be profound and lifelong. The tragic reality of birth injuries stemming from delayed C-sections underscores the immense responsibility placed on obstetricians and their teams. They must vigilantly monitor labor, accurately assess risk, and act decisively. This is to ensure the safest possible outcome for both mother and child. In such unfortunate circumstances, families often seek legal recourse. They bring medical malpractice claims, aiming to secure justice and provide for the extensive care their child will require.

You can read Blog posts on medical malpractice birth injury case Verdicts that involved a delay or failure to do a C-section, including:

- Pitocin Misuse $951M

- Prolonged Labor $48 Million

- Fetal Decelerations $29M

- Preeclampsia Stillbirth $25M

- Delayed C-Section $18M

- Placenta Percreta $17M

- Infant Death $16M

If you have any concerns or questions about C-section medical malpractice and birth injury, then visit the Kopec Law Firm free consultation page or video. Then contact us at 800-604-0704 to speak directly with Attorney Mark Kopec. He is a top-rated Baltimore medical malpractice lawyer. The Kopec Law Firm is in Baltimore and pursues cases throughout Maryland and Washington, D.C.